In choosing South Africans over Afghans, Trump valorizes race over service

A vivid argument on what citizenship means: Racial belonging, or commitment to an idea

The question of inherent worth versus earned worth is an ancient one – at least as old as David v. Ishbosheth.

This week it played out in an especially ugly way.

Donald Trump valorized white South Africans for being white while preparing Afghan refugees for deportation who risked their lives for America because, well, they’re not white.

Axios, in its pithy Axiosese, aptly called it a “split screen”. Here in real time was a vivid argument on what citizenship means: Racial belonging, or commitment to an idea?

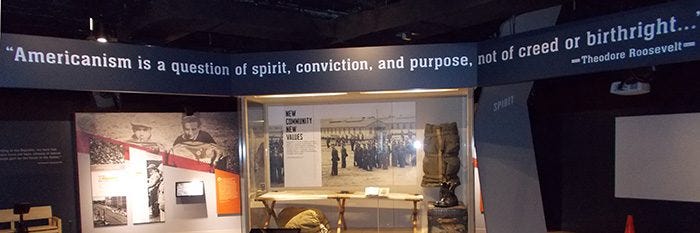

The jarring elevation of rank racism over patriotic duty recalled for me one of Washington DC’s hidden gems, a paean to the triumph of patriotism over race identity: the National Museum of American Jewish Military History, tucked into a small building on R Street off of Dupont Circle.

I first encountered the museum, run by the Jewish War Veterans of America, in 2008, when Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz organized a tour of the museum for Jewish Congress members and for the Jewish media.

I remember being moved by the museum’s intimacies: dog tags and uniforms handed down over generations, Jewish prayer books, thick and pocket sized and faded and still redolent with the hopes soldiers had for their safe return home.

Dog tags conventionally signified the soldier’s faith so the chaplaincy could apply the correct rites. During World War II, the military suspended the practice to protect any Jewish soldiers captured by the Nazis. Some Jewish soldiers defiantly scratched “J” onto their tags anyway.

I also recall an animated discussion between a trio of veterans who acted as docents: Jews were overrepresented in the military, if anything, they all agreed.

I learned over time, this insistent conversation was a feature of Jewish war veteran gatherings. The “if anything” was key: Jewish veterans lead a sisyphean battle against the impression that Jews shirk military duty.

“Time and time again, we have to remind our fellow Americans, ‘Yes, we were there,'” Col. Rich Goldenberg of the New York National Guard said a decade later at a Jewish War Veterans Shabbaton.

Goldenberg noted then that around the same time the Jewish War Veterans of America was established, so were similar societies elsewhere, in Britain and in Germany.

The timing was not coincidental: race-based nationalism was gaining traction.

“We’ve always been the outsiders looking in in the lands we’ve lived in,” said Goldenberg.

The best efforts of Jewish veteran groups notwithstanding, the trope persists, at times, God help me, perpetuated by Jews.

In Nazi Germany, World War I veteran status protected some Jews – until it didn’t. Race identification eventually trumped patriotism, and the valorous became victims. One of the lies perpetuated by Theresienstadt, the concentration camp presented to the world as a resort, was that it pampered German Jewish veterans,

The tension between fighting for an idea and preserving racial privilege was evident to the Black soldiers who fought fascism in World War II, according to surveys of troops uncovered only in recent years.

“It is impossible to understand how the brains of the Southern white man works and just what can be the cause of so much … hate that is imposed upon the Negro soldier,” The Washington Post quoted a Black soldier as saying in a 2021 story on the find. “With all the patriotic speeches … he takes time out to heap insults and abuse upon the Negro soldier who is doing all that he can to further the war effort.”

(I was considering a follow-up story about antisemitism revealed in the same surveys – it was pervasive although Jewish service in World War II outpaced the general population.)

The grimmest manifestation of the tension between Black service and white supremacist hatred were the Black soldiers in uniform who were lynched precisely because their uniform – their hard-earned status – was considered an affront. There was a lynching of a black soldier on a U.S. army base - but the FBI failed to determine who killed 19-year-old Pvt. Felix Hall. .

The lynchings, thank God, abated, but the racism and the obtuseness to it persisted, I learned in 2002 when I wrote for The Associated Press about the paucity of Black troops in Special Forces.

That year, almost four decades after the civil rights upheaval, white officers and analysts suggested that most Blacks were not up to the job – and that with a few exceptions the handful who did get into the elite units were getting a pass.

It was a familiar refrain for Black troops. "That's code for `You're not quite as smart, you're here because you're getting a break somewhere,'" said Brig. Gen. Remo Butler, a Black soldier who headed Special Operations Command-South.

How I got to Remo was telling: two of my white interviewees, the ones who were insisting to me that Special Forces were all about merit, said I should speak to him, he would set me straight about how there was no racism in the military.

Both called me back stunned after my story appeared. Apparently, they had never actually asked Remo about what it was like to be Black in the Special Forces.

Military service, with its prospect of the ultimate sacrifice, is the starkest stage on which a society determines whether it valorizes birthright or merit.

Perhaps its best known fictional representation is “Gunga Din,” by Rudyard Kipling. The Indian field aide sacrifices his own life to save the life of the narrator. “You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din,” the soldier finally reckons. In the world of Kipling, who valorized the British idea (he wrote an ode to the Magna Carta), the realization that one earns rather than is born into valor comes too late – but is no less acute.

Kipling was hardly woke. His work was infected by racial condescension. Sentimental valorizing of dead troops of color begs the question – why shouldn’t every non-majority citizen enjoy full rights, whether or not they serve?

It’s a question embedded in the Israeli and pro-Israel valorization of Druze and Bedouin troops. The encomiums to non-Jewish Israelis who serve can be as cringe inducing as a dramatic recitation of Gunga Din, but at least they carry within them the kernel of a democratic idea: A country is worth loving, worth dying for, not because its people share the same genetic makeup, but because of the equality, the coexistence, the redemption for which it strives.

It’s not a stretch that those who serve but who do not yet enjoy the full benefits of citizenship do so according to an unwritten compact: One day, this country will be worthy of your sacrifice.

“During my combat service in Afghanistan, local Afghans protected my unit and helped us return home,” Rep. Jason Crow, the Colorado Democrat and veteran, said this week. “We promised to protect them. The Trump administration is breaking that promise.”

Yes. And why it’s breaking the promise is stunning. Asked about the different treatment of the Afghans and the South Africans, Christopher Landau, the deputy secretary of state, said one of the criteria for refugees is that “they could be assimilated easily into our country.” The Afghans won’t be easily assimilated when they return to a country run by a vicious sect that sees them as traitors.

Trump denies race is a factor in his consideration. Yet he mimics the specious white supremacist claim that a “genocide” is underway in South Africa. (Trump is meantime seeking to deport people for accusing Israel of genocide.)

More to the point, he has gutted refugee protections for other vulnerable populations whose sin apparently is that they could not be “easily assimilated” – he has counted out entirely any intake of Palestinians.

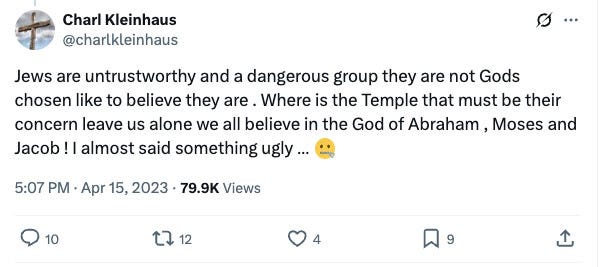

One of the South Africans named in interviews is Charl Kleinhaus, who purports to have been threatened with property confiscation. The most recent repostings on what appears to be his Twitter account are effusive praise for Trump, which is understandable enough.

Not so understandable is what the account tweeted in 2023: “Jews are untrustworthy and a dangerous group they are not Gods chosen like to believe they are.”

Assimilate that.

UPDATE: Kleinhaus just deleted his tweet. Here’s a screenshot.

Will said , thank you Ron for calling it out. So disturbing Cool to know about that museum in DC.

Thoughtful piece, Ron. Thanks!